In Japanese, for instance, the sentence "Hanako will come," includes the politeness marking "mas" in a formal setting-"Hanako-ga ki-mas-u"-but not in an informal setting. In his 2017 book, "Agreement beyond Phi," also published by the MIT Press, Miyagawa drew on Basque and Japanese to analyze "allocutive agreement," in which verb endings change based on the social status of the people being addressed.

In his 2010 book, "Why Agree? Why Move?," published by the MIT Press, Miyagawa made the case that agreement was more common than people realized, drawing on examples in Japanese, English, and Bantu languages. "Syntax in the Treetops" is the third book Miyagawa has written while building his case about agreement and syntax. "I'm extending the role of syntax, from just creating sentences to helping sentences be located in the proper discourse context, by connecting the sentence to the speaker and the addressee," Miyagawa says. The book extends other research and analysis he has been conducting over the last decade about the way the way agreement signals a bigger role for syntax in common language. That is the main argument Miyagawa makes in the new book, "Syntax in the Treetops," published today by the MIT Press. Rather than just being the machinery generating sentence structures, syntax also offers contextual information that can be of use to those uttering or listening to statements. And syntax, Miyagawa contends, has a more expansive definition than many linguists credit it for. The answer, Miyagawa believes, relates to a bigger issue in linguistics. You know that just from saying, 'Mary.' But with the agreement system, that same information is repeated on the verb." It repeats information to say the subject 'Mary' is feminine, singular, and third person. "Language is a remarkably economical system," Miyagawa adds. Agreement, he says, is essentially "redundant" information.

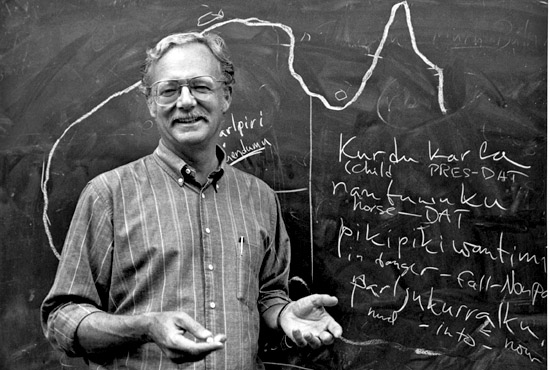

"It's a real mystery as to why this system we call agreement occurs in so many human languages," says Miyagawa, a post-tenure professor of linguistics and the Kochi-Manjiro Professor of Japanese Language and Culture at MIT. But one question that can be asked-Miyagawa has been asking it frequently in his recent scholarship-is why agreement is even necessary. Here, "haideţi" is second-person plural. MIT linguist Shigeru Miyagawa contends that it does just that, in a new book exploring the function of syntax, the principles through which language is constructed.Ĭonsider, first, that "haideţi" is a form of "hai," a sentence particle that inflects for person and number. But in the process, it might provide interesting evidence about the way everyday language works. I also love to knit, cook, play the piano, hike and travel, when there is no pandemic, especially for fieldwork: it never hurts to work on languages that are spoken in beautiful places.Uttering that sentence might not actually spur anyone into action. When I procrastinate, I watch films or read (predominantly, Russian and German literature, but, to repeat myself, I hope to make this list longer in the future). Most of this research would not have been possible, if not for Moscow State University fieldwork trips lead by Sergei Tatevosov and Svetlana Toldova, which I have been participating in since 2010.

I have worked on Turkic, Mongolic, Uralic, Algonquian and Austronesian languages, and intend to make this list longer in the future. I'm interested in a variety of topics in different sub-fields of linguistics, including lexical semantics (argument structure, event semantics, root modality, aspect, temporal adverbials and maximality inferences) compositional semantics and pragmatics (discourse anaphora, presupposition projection, focus/topicality and the semantics of A/A'-dependencies) syntax and prosody (strong islands, nuclear stress) and morphosyntax (concord and template morphology). I love doing linguistic fieldwork, and field elicitation is my preferred way of doing research.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)